Arlington, Virginia, September 2024

While I was brushing my teeth yesterday morning and (simultaneously) giving myself a pep talk about finishing this article, a book title came to mind: Ursula Hegi’s Stones from the River. I read this in a book club over twenty years ago. This novel has a habit of surfacing in my mind every so often. That may be because of the increasingly unruly (or is it savage?) time we live in. What always comes up for me is Hegi’s description of how the twin infections of fascism and antisemitism slowly crept step by step into the neighborhood, town, and country. Hegi shows the steps. We now can see the steps in our country and this book banning mania is one step. As I mentioned in an earlier post, that does not mean I think everyone should read every book. What I mean is that no single entity (e.g., local school board, do-gooder/know-it-all organization, etc.) gets to adjudicate for everyone else what they are allowed to read. Or, as I used to tell my children: de gustibus non est disputandum.

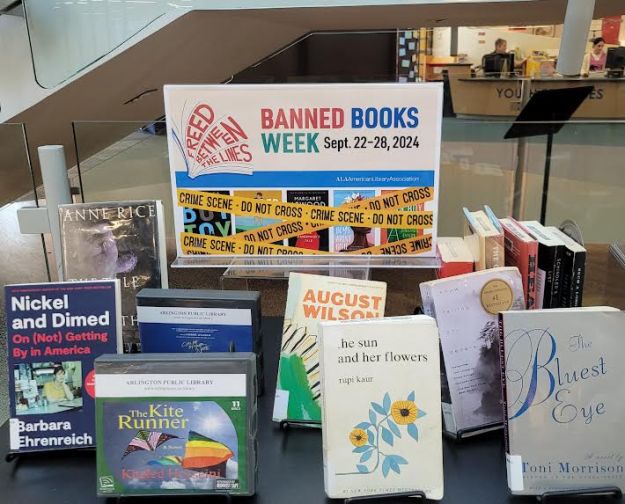

I feel lucky to live in Arlington County, Virginia where our Arlington Public Library supports our community–from story hours, used book sales, and providing access to free income tax help to free concerts, hosting distinguished authors (like Art Spiegelman, Jacqueline Woodson, and Jesmyn Ward), and being an official “book sanctuary.“

Now, I need to leave the comfort of my liberal bastion (see above) and go back once again to a different time and place: Page, Arizona, 1972-1973. I have written on this blog about Page before. One might reasonably think that, by now, I would have dissected this single year of my life until it is nothing but a pile of desert-bleached bones. Not so. It’s crazy, but after all my years of remembering my experiences in Page (many pleasant and all instructive), I have just recently come to a clearer understanding. As you will see from my account below, I fell into the clutches of a system that believed that I was an unsuccessful teacher because I didn’t follow the school’s rules of what I was supposed to teach. Even though I quickly realized that I was a good teacher (even in Page), I see I have some niggling trauma about my apparent failure (in the eyes of the system). I hope finishing this article may let those bones finally rest.

Banned Books Week, Arlington Central Library, September 2024

Read Whatever You Want Banner Arlington Central Library

Page, Arizona 1972-1973*

I taught eighth grade literature for one year (1972-73) in Page, Arizona. Following in the footsteps of my Milford teachers, I tried, inexpertly, to connect with the students and their lives. On a certain level, I did not prosper there. The authorities almost ran me out of town on a rail (not exactly, but they didn’t want me back). In other ways, maybe it was okay for both the students and for me.

One of my ideas was to augment the bland class textbook with a pile of books the kids might actually want to read. This is not a novel (haha) idea, but there were some complications. Although I was supposedly teaching literature, some students could not read well at all and many others were not up to what I thought was “eighth grade” reading level. Some students were (what we now call) English language learners: Navajo, Hopi, and Apache. Some were children of the construction workers who had come into town to build the Navajo Generating Station. Still others were the local Anglo kids whose parents worked at the Glen Canyon Dam, for the National Park Service, other Federal agencies, for the state, and in other, mostly white-collar, jobs. So, some kids could read nothing much and some were The Lord of the Rings aficionados along with me. My school-owned lodging cost next to nothing, so, with my schoolteacher salary, I was comparatively flush. I went to Babbitt’s (the main store in town back then) and bought paperback books such as The Green Grass of Wyoming, Wild Animals I Have Known and the High Adventure of Eric Ryback and some kind of age-appropriate book on sex. At some point, I also sent away for forty copies of Johnny Tremain, a particular favorite from my own childhood.

While we all slogged through the class text, lots of kids [and there were lots of kids– about thirty in each of my five (or was it six?) classes] read the paperbacks in the back of the room. I remember two sisters. They were barrel-racing, horse crazy girls who seemed to like The Green Grass of Wyoming as much as I did. They gave me a desert tortoise that lived and died in the closet of the barracks-like apartment I shared with a strait-laced school librarian.

I digress, but this is the most important part about the books at the back of the room I was shocked when I found that the only kind of books the school library had about Native Americans was schlock like Little Feather Draws a Bow (I made up this title because I can’t remember the actual titles). So, I put my anthropology and other books about Native Americans on the shelf at the back of the room. Some of those books disappeared and that was a good thing. I hope they were of use to the children and their families.

Somewhere, I acquired Forgotten Pages of American Literature. (Gerald W. Haslam. 1970. Boston: Houghton Mifflin). This book was an anthology of Native American, African American, Asian American, and Latin American literature. The book’s dedication, in memory of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., quotes the dream:

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but the content of their character.

I was so earnest back then and I loved these lines. Besides the bookshelf at that the back of the room and the poetry or song lyrics I would write on the board each day, I also tried to inject some more varied readings and ideas into class. I think (but am not sure) it was the Haslam book and some others (one of African American poetry, I think) that I wanted to use to give the students something more filling than wonder bread.

You would have thought that I would have been smarter than having one of the teacher’s aides copy the pages from my books for the kids. It turns out that some of these books had cuss words or some other “objectionable” text in them. The aide, a good church woman (although without the guts to confront me about my transgressions) ratted me out to the principal.

Let me confess here another text that also got me in trouble. I had the temerity (or congenital naiveté) to teach Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” to thirteen- and fourteen-year old students. With that story, we probably had the best class discussions of the whole year. However, I was hauled out in the middle of class one day and had my ears pinned back for presenting such inappropriate material. Never mind that I had first read that short story in sixth grade back in my little town of Milford. When I presented that defense, the principal schooled me, I guess, in the differences between Page and what he imagined was my sophisticated eastern school. (Milford, MI?) He did not fire me on the spot for my transgressions, but said I would not be teaching again in the fall. Note: It turned out okay as I received a teaching fellowship at the University of Utah for the next year.

Bottom-line: The ethnocentrism was palpable in that school in Page. Not just addled teens, but experienced teachers talked about dirty Indians and about which indigenous groups were smarter or better than others. I hated that, and I hope things have changed. I do remember, though, at our class party T____, the pretty Anglo cowgirl slow-danced with E___, the handsome and very funny Navajo boy. MLK, this dance is for you.

Forgotten Pages of American Literature

Conclusion

I find myself at the end of this third “Book Talk” with no great pronouncements about the socio-political intricacies of banning books. I do remain angry about people and entities egregiously telling others what they should read, or think, or believe. I am no anarchist: I believe in formal and non-formal institutions and appropriate, reality-based authority/ies under the guarantees of the The Bill of Rights. I love children, schools, books, and libraries–museums, too, for that matter. I want children–in sensitive, age- and culturally-appropriate ways–to learn. That means learning all sorts of things: the multiplication tables, the carbon cycle, how to swim, and the factual history of our country, world, and the universe. Especially, I want children, and all of us, to learn about how we can all be different–age, gender, ethnicity, abilities, interests, everything–and that that is the good way for our society to be.

You see, I am still naive, idealistic, and hopeful, even now.

Tom just texted that he is picking up the new Kwame Alexander book for me. I can hardly wait.

Happy autumn and please vote.

*adapted from Losing It: Deconstructing a Life, unpublished work © Lynda Terrill, all rights reserved